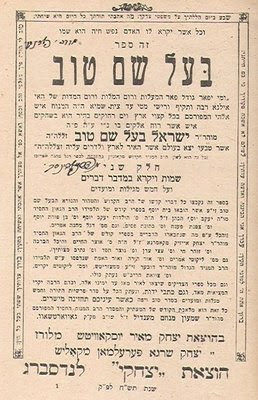

(Picture by moshebyny)

This unedited translation belongs to the Breslov Research Institute (BRI), which commissioned me to do a collection of such translations for the forthcoming revised edition of “Uman, Uman, Rosh Hashanah,” a practical guide for travelers to the Breslover Rosh Hashanah Gathering in Uman. It is posted here by the kind permission of Rabbi Chaim Kramer, director of BRI.That winter [in 1811, following Rebbe Nachman’s passing], as the month of Shevat approached, Reb Noson began to yearn to travel with at least a

minyan to the Rebbe’s

tziyun (grave site) in order to pray there on

Erev Rosh Chodesh. This month is one of the four “Rosh Hashanahs” mentioned in the Mishnah, and the Rebbe had declared, “

Gohr mein zakh is Rosh Hashanah . . . My entire mission is Rosh Hashanah.” Therefore, Reb Noson wanted to use this opportunity to encourage the other Breslover Chassidim to start thinking about traveling to Uman for Rosh Hashanah the coming Tishrei, concerning which the Rebbe had spoken so urgently prior to his last Rosh Hashanah.

Reb Noson succeeded in persuading a few fellow Chassidim in the town of Breslov to join him on the journey. There were no trains to take in those days; so he hired a coach and horses and arranged to pay the driver by the day. The driver agreed to go wherever he was told, even if Reb Noson wished to go to Uman in a roundabout way, or to spend the night in one of the villages. When they had travelled only a mile or so from Breslov, Reb Noson instructed the driver to turn toward the village of Sidkovitz, and not to take the usual route through Heisen. No one in the coach understood what Reb Noson had in mind, including the driver, but the latter had to oblige in keeping with their agreement. They arrived in Sidkovitz when it was almost time for the Minchah prayer.

A Breslover Chassid lived in this village, a follower of Rabbi Shmuel Isaac of Dashev, who had come to Uman to be with Rebbe Nachman on his last Rosh Hashanah. Reb Noson told the group that there they could

daven Minchah. When they came to this man and he saw Reb Noson and the other Breslovers at his door, he was so happy that he immediately covered the dining table with his best tablecloth and lit candles as on the Shabbos in honor of his distinguished guests, particularly Reb Noson. Full of joy, he placed a bottle of spirits and a bottle of wine on the table, as well as cakes and sweets.

After they concluded the

Minchah prayer, they saw that it was still possible to continue on to the next village and spend the night there. However, Reb Noson told the Chassidim, “We have a ‘business partner’ here in the inheritance that was left to us.

Nu, we must talk things over with him, so that he should know what a lucrative business this is!”

The host begged everyone to sit and partake of the refreshments he had served in their honor. However, the time to

daven Ma’ariv had already arrived. Reb Noson said that it was prohibited to eat a meal before praying. So they prayed

Ma’ariv together then and there. The host was greatly inspired by the prayers of Reb Noson and the Chassidim, who

davened with fiery enthusiasm and clapped their hands, but he still did not understand why they had suddenly appeared. He thought to himself, “Just seeing and hearing how my fellow Chassidim pray

Ma’ariv this way, despite their weariness from the journey, when even in the town synagogue the worshippers don’t pray with such intensity – it would be sufficient!”

After

Ma’ariv, they all sat down, and the host invited Reb Noson to taste the good food and drink he had served. However, Reb Noson said, “Before we eat, there is something that I would like to say.”

He arose from his seat and addressed his host. “You were present at the last Rosh Hashanah of the Rebbe’s life, together with the holy assembly. And many of us heard from the Rebbe’s mouth on that Erev Rosh Hashanah that he wanted each one of his followers, wherever they resided, to cry out that whoever wishes to be a truly good Jew, an ‘

ehrlicher Yid,’ should come to him for Rosh Hashanah in Uman. He said, ‘I myself had a mind to pick myself up and go away…’ [However, he decided not to do so because he looked forward so much to Rosh Hashanah . . . He told his followers, “I want to remain among you – and you should come to my grave” (

Tzaddik #94)].

“At that time, he also said, ‘To me, the main thing is Rosh Hashanah. What can I say? There is nothing greater!’ In the final lesson he delivered on that Rosh Hashanah (

Likutey Moharan II, 8), just before he passed away, he spoke about how one must pray to God to be worthy of drawing close to a true leader in order to attain perfect faith. Similarly, in the lesson on the subject of the prostok (‘simple peasant,’ published as

Likutey Moharan II, 78), he stated that one must beg God to bring one close to the true tzaddik – and this was on

Shabbat Nachamu, when the Rebbe was already gravely ill and knew that he was about to die. Nevertheless, he spoke this way. Plainly, all of these statements and urgings were about our continuing to come to him for Rosh Hashanah, even after his passing, until the arrival of our righteous redeemer! The Rebbe warned us that the Evil One in his deviousness established false leaders in the world, so that one doesn’t know where Moses can be found, or where Aaron can be found, namely the true leaders. For this reason, my beloved friend, we came here to forge a mighty, lifelong bond among ourselves concerning this good inheritance that remains with us!”

Then Reb Noson asked the Chassidim who had come with him to sing “

Ashreinu, mah tov chelkeinu, how fortunate are we, how good is our portion (

yerushaseinu)!” For the Torah is our inheritance (

yerushah), as it is written, “An inheritance (

morashah) of the congregation of Yaakov” (Deuteronomy 33:4) -- and their host’s name was Yaakov.

They danced and danced to this song, and then returned to their seats at the table. The host filled a schnapps glasses for Reb Noson, and then Reb Noson shook his hand and drank a “

l’chaim” to him. Then he told him, “With this handshake you agree to travel every year for the rest of your life to the Rebbe’s holy

tziyun for Rosh Hashanah and be numbered among those who participate in the holy Rosh Hashanah gathering in Uman!” And the host replied, “Amen, may this be God’s will!”

Reb Avraham Sternhartz [who preserved this story] added that during his youth, he met the grandson of this man, who also traveled to Uman for Rosh Hashanah. He told how his grandfather had written in his will that every year his son should come together with his sons to Uman for Rosh Hashanah. (

Tovos Zikhronos, pp. 129-130)

===========

May Hashem provide all of the travelers to Uman this year and every year with all of their needs, materially and spiritually; protect them all both coming and going; inspire them and enable them to make a new start in avodas Hashem; and bless them, their families, and all Israel to be “written and sealed for the good, amen!”